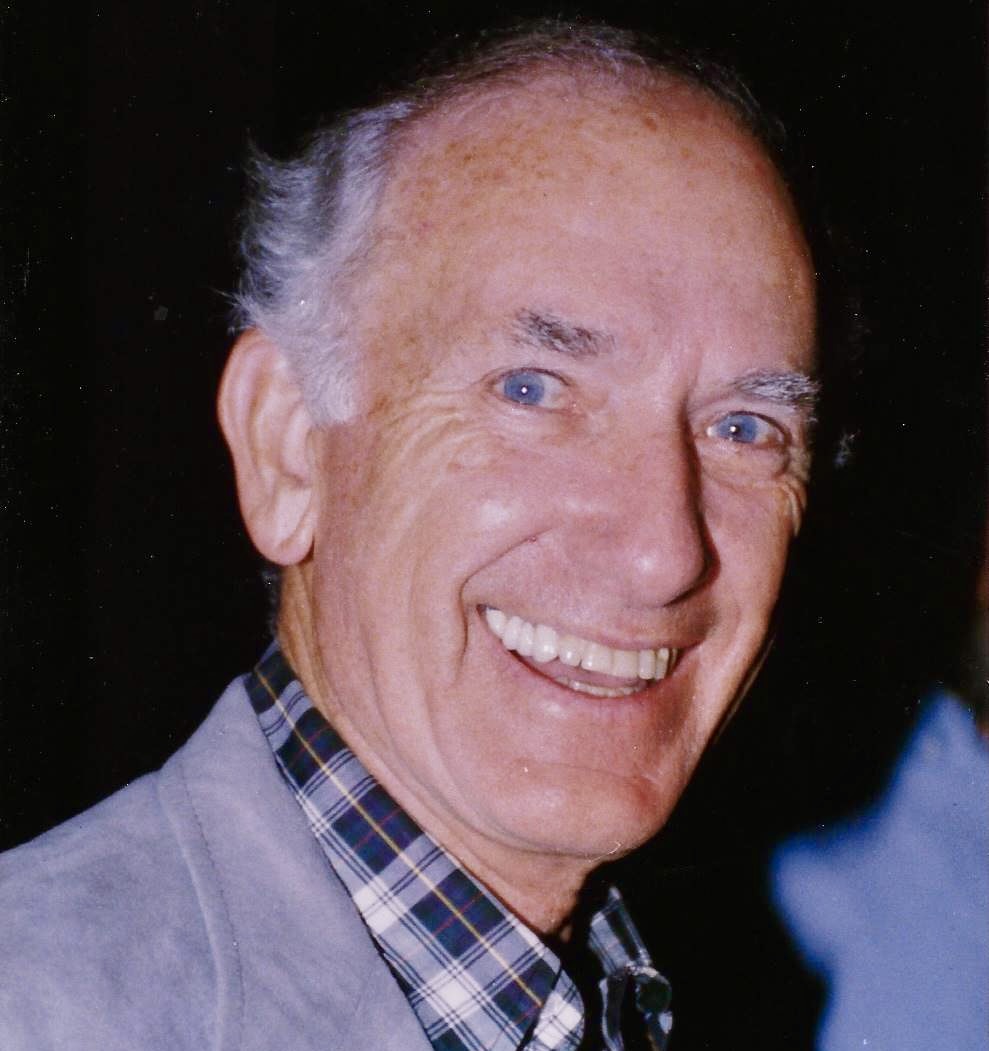

Clancy Brazill.

Welcome to the sixth in a series about McCleskey’s history … this chapter on the 1970 Lubbock tornado. A separate story on the rest of the ’70s will follow soon.

Chapter 1: Firm’s beginning.

Chapter 2: 1930s.

Chapter 3: 1940s.

Chapter 4: 1950s.

Chapter 5: 1960s.

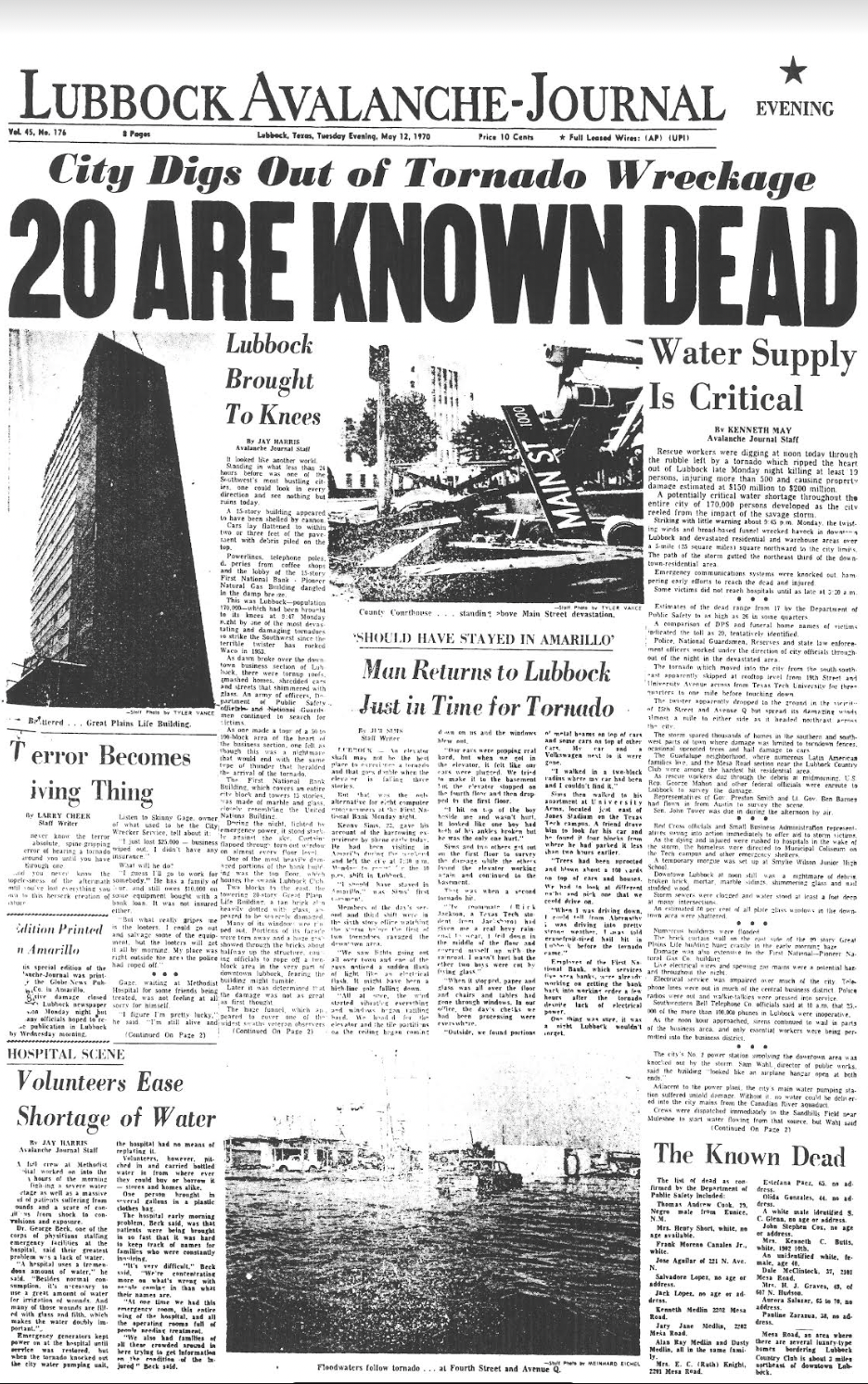

The following was taken from the late Clancy Brazill’s oral history at Texas Tech University’s Southwest Collection, interviews with Don Graf, Mary Cato, Ruth Anne Brazill and a U.S. Department of Commerce report on the 1970 Lubbock Tornado.

Tornado warning in effect

Weather Bureau, Lubbock, Texas

Issued at 8:15 p.m., May 11, 1970

A tornado warning is in effect until 9 p.m. for persons in Lubbock, Western Crosby, Eastern Hale and Floyd counties. A funnel cloud was sighted by an off-duty policeman at 8:10 p.m. and radar at Weather Bureau indicated hook configuration also at that time located 7 miles south of Lubbock airport and moving northeast.

More than an hour later, Clancy Brazill was flung to the ground on his back, watching books fly over his head on the 19th floor of the shuddering Great Plains Life Building as killer multiple-vortex tornadoes tore through Lubbock.

Twenty-six people died on Monday night, May 11.

Attorney Brazill survived, but the Nelson, McCleskey & Harriger law offices did not. Brazill was working, stopping for a sandwich around 7:30. When he came back to the firm’s perch above downtown he saw an enormous buildup of clouds southeast toward Slaton.

By the time Brazill wanted to go home around 9:30 it was raining hard. He decided to wait until it eased. Then came hail. The building started to sway a bit – not unusual in windy West Texas. The hail was unusual. The Pennsylvanian had heard of Texas-size hail in the almost decade he’d been in Lubbock and thought this was a real-life example of those tales. Brazill backed away from the windows. The hail was so large and hitting the windows with such a racket he feared they would shatter the glass separating him from the torrent.

He stopped to answer the phone. It was his wife calling to report severe weather at their home on 9th Street just off Quaker Avenue, afraid the front windows were going to shatter from the pounding hail.

Brazill told her the situation as the office was the same as she was seeing.

He was ready to leave.

Weather Bureau, Lubbock, Texas

Issued at 9:14 p.m.

Radar indicates this to be a severe hailstorm. Several reports in the past 10 minutes indicate golf ball- to baseball-size hail in the vicinity of the Holiday Inn.

Out go the lights

The lights went out, then back on. He got off the phone, feeling the building buffeted from what was later called an F5 tornado.

Brazill dashed across the firm’s law library, got through a door into the hallway in the middle of the building. That’s when he was knocked down. He had no idea what sent him to the ground – was it the building shifting in the winds that may have come close to 300 miles per hour or did he just stumble?

He saw law books flying overhead like a scene from a movie and blue papers – possibly invoices from a trial. Dust also flew past which he later realized was from ripped-apart walls.

Then the lights went out for good.

Brazill got to his feet. Now the tallest building in Lubbock was fiercely shuddering back and forth like someone walloping it with a giant baseball bat. He began to worry it could either topple or disintegrate, not sure what was keeping it standing as he heard tremendous crashes of breaking windows and building pieces.

In the darkness, he headed for the glass entrance doors to find them locked – which cleaning crews did. Brazill had his key ring and groped for the keyhole – not made easier by the violent shaking. He spread his feet apart for more stability trying every key twice with success on his third attempt. After opening the door, he felt around for his coat he’d dropped while trying to open the door.

9:46 p.m.:

Power failure at Civil Defense Headquarters.

9:47 p.m.:

The last communications between Lubbock WBO and Lubbock Civil Defense reported that “hooks” were indicated on radar about 9:45 p.m. about 5 miles southwest of Lubbock.

9:49 p.m:

The Lubbock WBO lost all communications.

9:55 p.m.:

Lubbock WBO personnel abandoned the WBO to take cover from the approaching tornado.

Descent in darkness

The stairwell was the only way down. Brazill grabbed a handrail, got a rhythm of the number of stairs to each landing and headed for terra firma in the darkness.

Every step felt closer to safety.

Around the 7th or 8th floor he came upon a group of people who’d been taking a real estate class on the 20th floor. They’d been halted by broken pieces of plaster on the stairs. There were several women in the group and were having trouble navigating the roadblock. Brazill hollered to ask if anyone had a match.

By now, the weather had eased. The building wasn’t shaking as it had when Brazill was trying to open the glass doors.

Two months earlier, Brazill broke his leg skiing, getting it out of the cast a week or so before the tornado. But he was able to get down the stairs with little problem.

He started to relax but then felt a tremendous knot in his stomach as it hit him what could have happened. Any immediate fright was temporarily pushed aside because he was too busy trying to get down from the 19th floor.

On the ground floor there were more broken windows. People had gone to the building’s underground shelter, but Brazill was focused on getting home to make sure his family was OK. He saw a man with a walkie-talkie, asking him to contact the firm’s phone answering service to call his wife so she knew he was OK.

A mess in the streets

Exiting the building’s west side on Avenue L, he walked in the rain and wind to see broken power poles and cars slammed into each other. There was a car outside the doorway that had been parked in one of the drive-through lanes for First National Bank.

Brazill got to his car parked behind West Texas Hospital, being careful to step over downed power lines. More cars were piled up around the area. His windshield was smashed and the back window blown out. But the tires still had air, the car started and he headed north on Avenue K. The debris got worse the further north he drove. At the time, he had no idea he was driving deeper into the hardest-hit area.

People were hollering for help to get out of a house around 8th Street – their roof gone. Brazill moved some debris blocking their front door. They wanted to get out, but the attorney told them they’d be safer staying in the house because of the downed power lines.

It took him 30-45 minutes to get to 4th Street, usually a drive of a few minutes.

He saw a boy whose arm was badly hurt with cuts who asked Brazill to take him to the hospital, but Brazill explained he could walk there faster because debris in the street made driving difficult.

The plan was to take 4th Street home, but debris was so bad he turned in another direction, going down a side street until his car went into a hole where an uprooted telephone pole had been. He couldn’t get the car – now with a flat tire – out of the hole. The rain was now heavier than when he left the Great Plains Life Building.

Brazill walked west, getting to Avenue Q where more decimated buildings showed the deadly storm’s impact.

Cement-block walls blown out. Roofs on wooden homes were blown off with the rest of the residence collapsed.

Then he saw the Fields Living Center, which Brazill had watched as it was built. They used prefab steel to construct what impressed the attorney as a solid structure.

It was beat down – a mess – looking as if a bomb was dropped on it.

Water around Avenue Q was so deep, Brazill removed his wallet from his trousers because it was up to his knees.

A man offered a ride home. But after a couple of blocks, the man got a flat tire. Brazill helped him fix the tire, but his car wouldn’t start because the high water literally flooded the motor.

Brazill started walking – across University, then by the Municipal Coliseum where he hitched a ride from a man with a boy, getting home around 1 a.m., more than three hours since the twister hit. When he asked the driver about damage to the west the man told Brazill there wasn’t any.

His house in the Rush neighborhood was fine. The lights were on, but his wife and kids had gone to an underground cellar at a neighboring doctor’s house.

Brazill later discovered he could have easily driven home if he went south to 19th Street.

Focused on a trial

Hours earlier, firm attorney Don Graf watched TV reports saying the tornado hit downtown, there was a lot of damage and people should avoid the area. He’d barely seen any rain around his neighborhood on 30th Street.

Graf was in trial all day, working with George McCleskey representing Lubbock Glass & Mirror in an anti-trust lawsuit against Pittsburgh Plate Glass. Graf planned to meet with his legal assistant after the trial ended for the day. But he was tired and asked if she could meet him at the office at 6 a.m. before court began.

He went to bed to be as rested before another day in court.

Next morning

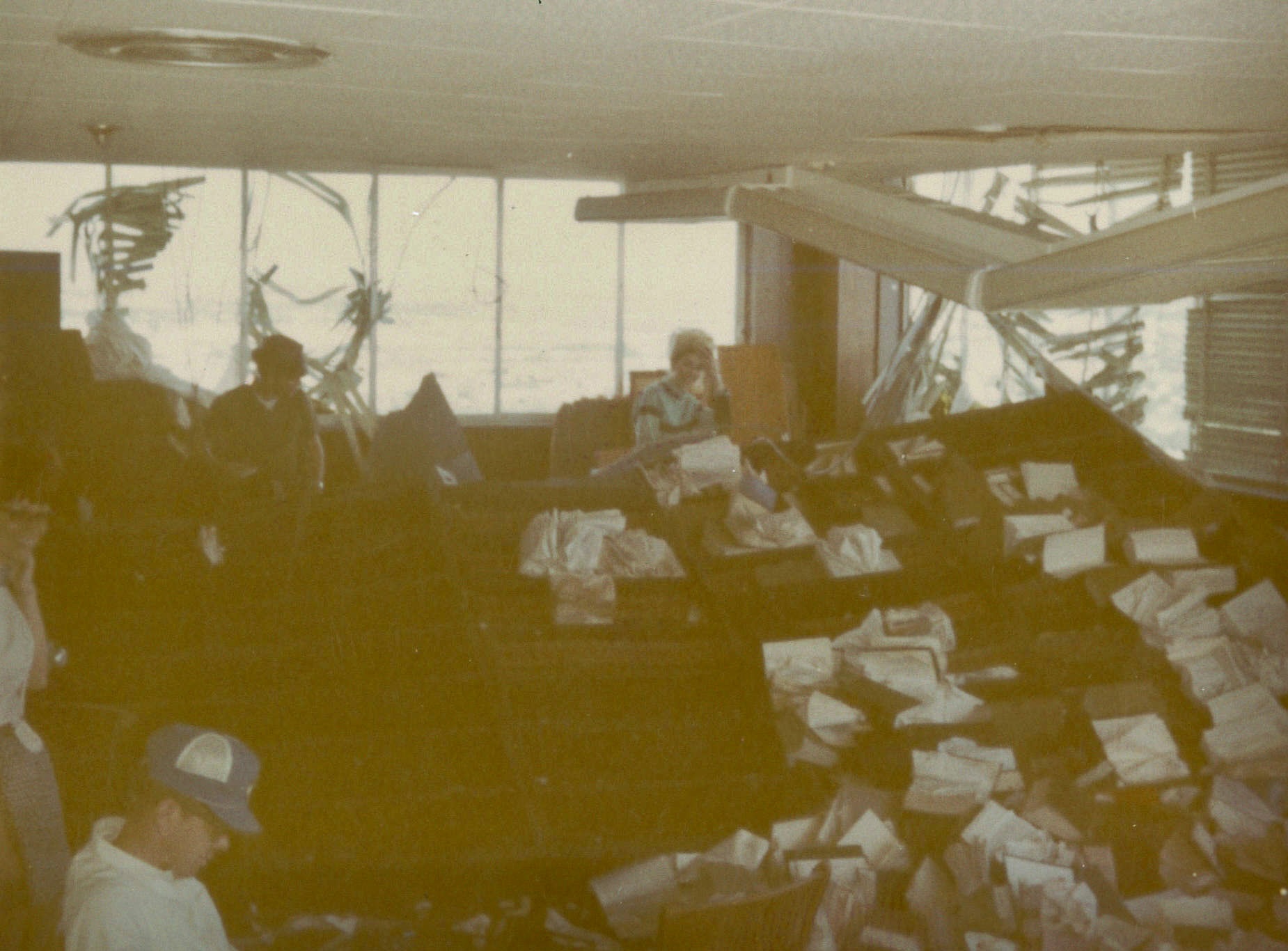

When Graf got to the building at 6 a.m. on Tuesday, May 12, there was no power. He walked up to the building’s roof with a maintenance man and looked over the devastation as the sun rose.

He wasn’t going to court in a few hours.

Brazill got up at 6:30, called partner Harold Harriger to tell him about the damage to the firm. Harold said, “What tornado?”

Graf walked down to the firm’s offices to see more destruction.

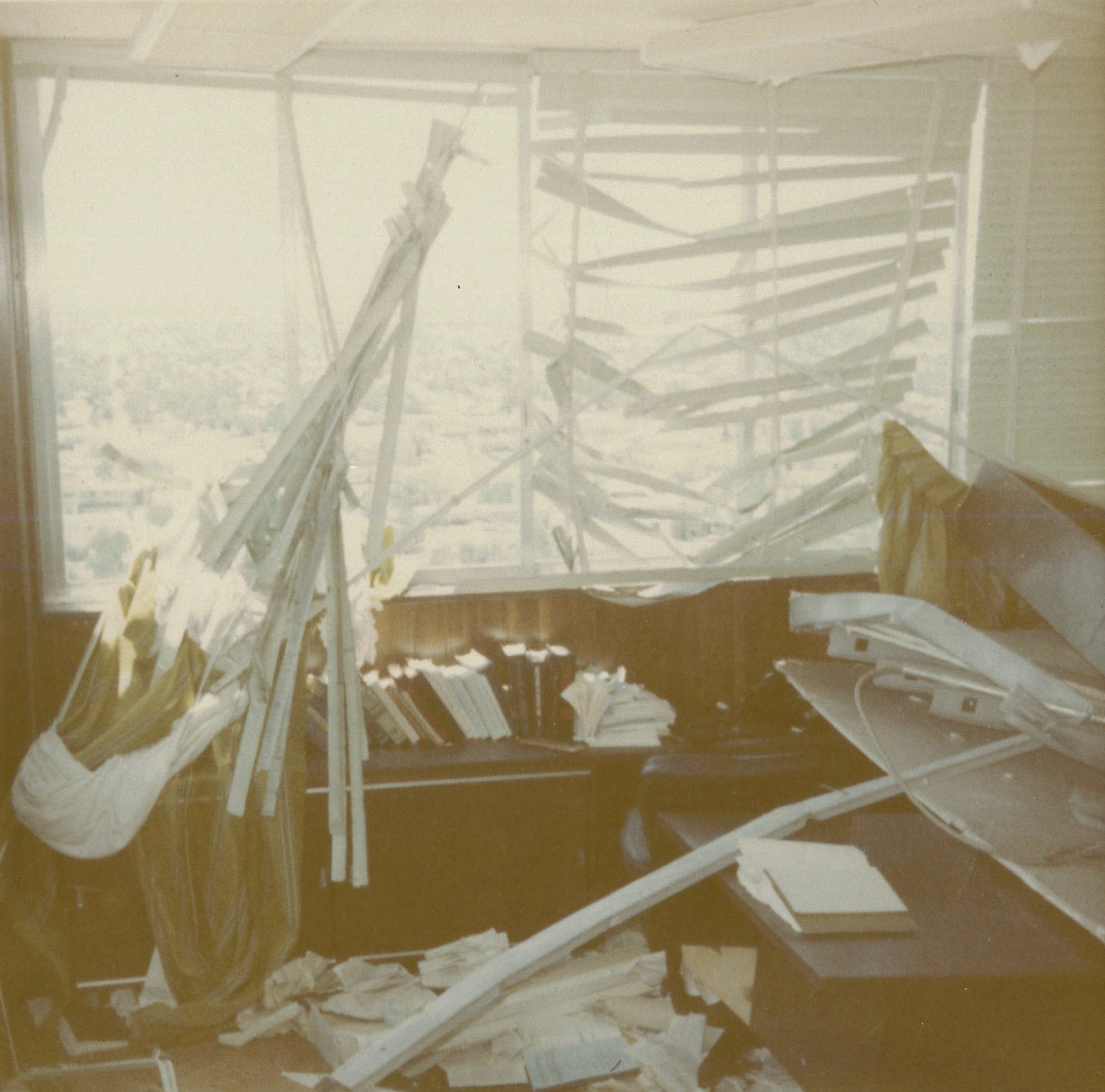

The south side of the 19th floor – McCleskey’s office and the law library – were hardest hit.

Graf went downstairs and found a working phone at a barber shop across the street, calling his legal assistant to tell her to not come in.

As attorneys and staff arrived, they huddled outside figuring out next steps.

Graf’s office was next to McCleskey’s but not damaged. Rex Aycock’s office was across the hall and was always tidy. There was one piece of paper on his desk and it got wedged between the wall and ceiling.

Brazill got a ride to the firm around 8. He was told they couldn’t get into the office, there were fears it could topple. So he went to the back door and up the 19 flights.

He was aghast at the tremendous damage and took pictures for insurance.

Brazill started to realize the danger he’d been in when he saw books up and down the hallway after the law library’s bookshelves were blown out. Books were piled under the receptionist’s desk, which was almost a half block away from the law library. Tremendous shards of glass along with marble- and pebble-sized pieces of glass littered the hall. He realized some of that glass went over his head, but he didn’t have even the tiniest scratch.

The interior walls of his office were torn out, furniture destroyed. Pictures gone from walls; desk drawers blown open.

The east wall of the library – full of hundreds of volumes in steel shelving – blew into George McCleskey’s office and onto his desk.

Some of the furniture Brazill was working on – large heavy oak tables –were lying next to windows. One of the table legs was hanging out a window, with a cord from office blinds wrapped around it.

Other things blew out of the 19th floor.

Some of Brazill’s books were found on buildings many blocks away to the east and north.

The entire library was destroyed – $25,000 in damage. The insurance company just packed up debris and carted it off. Pages were fused together from the water, bindings gone. The firm bought a new library from the insurance payment.

Fortunately, the file room was not destroyed in the 19th floor’s northeast area. That’s also where firm founder Hobert Nelson’s office was. Nothing was disturbed.

Walls bulged, doors were slammed shut from the force and couldn’t be opened.

Later that day, Brazill went with a friend who owned McDonald’s restaurants in town delivering coffee to volunteers. Brazill kept telling his friend, “I can’t believe I lived through this.”

McCleskey and Graf checked in with the judge on their lawsuit. The judge said none of the jurors were seriously affected by the tornado. They’d already been in trial three weeks, with about two more weeks to go. He asked the attorneys if they wanted to start over. Not acceptable. So they were back in trial Wednesday, May 13. The day before Graf carried his assistant’s electric typewriter down 19 flights so she could prepare materials for the trial.

That was also the same day the firm opened for business in a building on 1801 Avenue Q owned by McPherson Mortgage, which was one of the firm’s clients. The office was sparse until more furniture and equipment came in over the next days.

McCleskey and Graf got off moving duty.

Brazill had been working on an appeal brief he was supposed to get to Amarillo.

Mary Cato called the clerk in Amarillo to explain the brief would not be submitted because Brazill lost everything he was working on when the library was destroyed. It took her most of the day to get a working line to call Amarillo.

The firm worked for the next week walking up and down 19 flights with stuff for their new office. There still was no electricity in their shattered offices. Brazill lost count of how many times they went up and down. But they needed lights in the stairwell, even in broad daylight the stairwell was completely dark.

Eventually, a big crane from Irwin Steel Erectors – one of Brazill’s clients – hoisted a platform with a box to the 19th floor to move the firm’s belongings.

Afterwards

- Besides the tragic 26 deaths, 1,500 people were injured, more than 250 people were seriously hurt, more than 10,000 homes were damaged and 1,100 were destroyed. The tornadoes left more than 1,800 Lubbockites homeless. Property loss was estimated at $840 million, or about $6.8 billion in 2024, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- President Richard M. Nixon declared Lubbock a disaster area on May 13 and Lubbock attracted more than $37 million in federal funds to rebuild. That led to the Lubbock Memorial Civic Center, the Mahon Library and a series of lake parks along Yellow House Canyon.

- McCleskey and Graf won their case against Pittsburgh Plate Glass, which had tried to monopolize the contract glass business in Lubbock. But the jury also found Lubbock Glass & Mirror was not damaged. Pittsburgh Plate Glass stopped what they were doing when the suit was filed two years before, so the Lubbock company had two years of relief. It was a victory and the client was pleased – but a somewhat Pyrrhic victory.

- Months after the tornado, someone found law books with Brazill’s name in them in Idalou and wanted to return them. And for a few years, if someone could not find a file, it was blamed on the tornado.

- Ted Fujita, a severe storm researcher from the University of Chicago, studied the Lubbock tornado and created the Fujita Scale, which identified tornado strength on a scale of one to five, based on wind speeds.

- A report on the tornado done by Texas Tech professors, eventually led to the university creating the National Wind Institute, which worked on making the world safer from winds that kill, injure and damage property. The professors also challenged the Fujita Scale, eventually leading to the Enhanced Fujita Scale, which flipped the process – looking at damage first, then wind speed.

- On the 51st anniversary of the tornado, a memorial was dedicated at Avenue Q and Glenna Goodacre Boulevard. It honors Tech’s “five wind science pioneers, who revolutionized wind sciences research and education” – Kishor Mehta, Joe Minor, Ernst Kiesling, Jim McDonald and Richard Peterson.

See Gordon Smith’s video of the tornado from Texas Archive of the Moving Image.