(Photo above: Harold Harriger and his daughter Melissa).

Welcome to the fourth in a series … this one about the firm’s history in the 1950s.

Welcome to the fourth in a series … this one about the firm’s history in the 1950s.

First part about the firm’s beginning.

Second part about the 1930s.

Third part about the 1940s.

He was a self-proclaimed Yankee from Harriger Hollow — in Pennsylvania coal mining country — lured to Texas by a brother who didn’t want him working in the mines like their daddy.

Harold Harriger eventually landed in Lubbock and joined what is now the McCleskey Law Firm in 1955, becoming one of its cornerstones over 50 years while setting an example of community service beyond billable hours.

Besides the Yankee’s arrival, the 1950s brought prosperity to the South Plains, as it did to the rest of the country, an exhale of relief from the challenging years of the Great Depression and World War II.

Lubbock was growing, from 71,747 in 1950 to 128,691 in 1960. More people meant more work for the law firm, including starting to represent United Supermarkets.

Lawyers at the firm — called Nelson, Brown & McCleskey at the beginning of the decade, with offices in the Lubbock National Bank building — expanded their practice and families.

Hobert Nelson was still a force and still politically connected, fielding calls from politicians like then-Senator Lyndon Baines Johnson.

In 1954, former FBI agent George Gilkerson joined for several years until he became a prosecutor and Lubbock District Attorney.

In 1959, Edward Smith became the firm’s tax attorney, filling a void when Franklin Brown and his son, Sam Brown, left in 1953.

After the Browns departed, the firm became Nelson & McCleskey. The final name change of the decade came when Harriger became a partner in 1958 and his name was added to the letterhead.

Another Nelson — Hobert’s son Bert — joined the firm toward the end of the ‘50s.

Also supporting the practice in the late 1950s were two legal secretaries — Naomi McGuire and Gail Etheredge — who started at a time they couldn’t wear pants. They spent their careers with the firm when they weren’t raising their families.

Lubbock in the ’50s

Lubbock’s growth was attributed to irrigation, Texas Technological College (now Texas Tech University) and its emergence as a medical and marketing hub, according to Paul H. Carlson in his book “The Centennial History of Lubbock.”

- Lubbock’s Reese Air Force Base, closed after World War II, reopened in 1949, employing 650 civilians and 2,800 airmen at its peak.

- Lubbock Municipal Airport attracted national airlines, stimulating growth.

- Better yield for farmers with irrigation brought related equipment business to the city, along with cooperatives to store and market cotton and other crops.

- The Furr’s companies — Furr’s Supermarkets, Furr’s Cafeteria and warehouse and wholesale grocery business — expanded to meet the population boom of the 1950s.

- After decades of trying, Texas Tech was admitted to the Southwest Conference in sports, sparking a massive celebration in the city.

- West of Lubbock, continued oil production at Slaughter Field, where oil was first discovered at the adjacent Duggan Field in 1936, bolstered the economy. The philanthropy of the DeVitt family, who owned the majority of the sprawling Mallet Ranch sitting atop part of the oil fields, supported culture and education in the area and beyond.

The Yankee from Harriger Hollow

Melissa Harriger Reeves recalled stories her father told about his early days.

Her parents had already moved to Lubbock’s Rush neighborhood when she was born in 1957, the oldest of the family’s four children.

In his last year of law school at the University of Texas in Austin, Harriger was looking for the best job he could find to take care of himself and his wife, Rebecca (Craig) Harriger and the family they would have.

“He felt like the best opportunity was here with Nelson and McCleskey, came here and jumped right in as you can see,” Reeves said.

Not only did he quickly make partner in 1958, but Harriger was a valuable community leader, serving many roles at:

- First United Methodist Church.

- Then-Methodist Hospital Board.

- Lubbock ISD board.

- United Way.

- YMCA.

- Rotary Club of Lubbock.

- Boards of Plains Capital Bank and the First State Bank in Shallowater.

Harriger was born in 1928, the youngest of 13 children — six sisters and six brothers. Harriger Hollow was about 80 miles northeast of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. While father worked in coal mines, his mother took care of their children and raised a garden feeding her family.

Reeves said a cousin has remodeled the house where her father was born. Her family inherited a smaller cabin belonging to her father’s uncles and aunts.

“It’s a perfect place to go for a little bit of time. The land is what he loved,” she said.

Like others in his generation, Harriger lived through the Great Depression, but Reeves remembered her father saying, “We didn’t know the Depression was going on because we were so poor.”

When he was 15 years old, his mother died and then he lost his oldest brother in the next two years.

Harriger served in the Army Air Corps for three years. Although he was deployed to Japan at the end of the war, he didn’t see combat, Reeves said.

Lured to Texas

Another older brother, Russ, lured Harriger to Texas after his service, asking him to bring his car from Pennsylvania to Wichita Falls.

“I think he knew that (Harriger) was smart and he didn’t want him to end up in the coal mines,” Reeves said.

Mining was a rough life. Reeves’ grandfather was a miner for most of his life, only coming home a couple of weekends a month until he lost his foot in a mine collapse.

Harriger got a job at a Wichita Falls gas station. His brother convinced him to enroll in Midwestern State. Harriger’s boss gave him hours to work around his classes.

Somewhere between college and the gas station Reeves’ parents met. Rebecca Craig’s first job was teaching music at a local elementary school. She also played bass for the local symphony.

Harriger joked “the only reason (Rebecca) dated him was because he drove a convertible and her bass would fit,” said their daughter.

They were from very different backgrounds but were married for 50 years until her mother’s death in 2000.

“I’m sure they had some explosions in the first five years. She was from a small family, a Methodist preacher’s family, a very quiet, very controlled environment. He was from chaos — a miner’s family with boys who ran wild on the farm and hopped trains to town.”

Together they went to Austin for Harriger to attend law school. They both became active members in the Methodist church there.

Harriger’s mother and his siblings had attended a Church of God. Reeves said she found a letter from her mother to her father making it clear if he wanted to be with her they’d be Methodist church members.

In Lubbock, they immersed themselves in the First United Methodist Church, where he was a lay leader and a Sunday School superintendent among many other roles. Harriger also became an attorney for the Northwest Texas Methodist Conference.

Her parents marriage inspired her, Reeves said.

“Another thing he taught me was the importance of a good marriage. It’s not that they were without conflict. I mean they were humans. He always told me never to go to bed mad.”

Harriger also brought his skills of mediation and dispute resolution to his career and everywhere he went. “I guess he learned that from being one of 13 siblings,” Reeves said.

“He always told me that I could do anything, be anything. He had absolute faith that I could do whatever I wanted. He expected you to do your best and your best was good enough. I would have done anything he wanted me to do, honestly.”

Another Nelson

Hobert’s son Bert Nelson joined the firm in 1958 after serving in the U.S. Air Force beginning in 1951.

Nelson served one year as a senior surgical nurse before he started flight training. In 1953, he was assigned to Military Air Transport Service Ferry Command, where he ferried bombers, cargo planes and amphibious aircraft throughout the United States, Canada, South America, Europe, Japan and North Africa.

In “A Library Full of Stories,” Nelson told writer Jane Bromley of Lubbock Senior Link that his military service was “great duty. No combat.”

After his discharge, the younger Nelson went to law school at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

After graduating and joining the firm, “I got more business in six months than I could handle,” Nelson recently told McCleskey partner Bill Lane in an interview.

Nelson was the only attorney in the office on a Friday afternoon when two men from Plains National Bank came by, asking the firm to bank with them.

“I said ‘everybody’s back itches,’ and they said, ‘you’d like to represent the bank?’ and I said, ‘hell yes,’” Nelson said.

On Monday, he told his dad and McCleskey he committed the firm to move its business to Plains.

McCleskey was upset, worried they’d lose business from the bank they’d been using, Nelson said.

“I said, ‘all $300 a month.’ He would have fired me immediately if it hadn’t been for dad,” Nelson said.

Nelson practiced for six years before deciding to follow a business career. One of his first ventures was buying the Dr. Pepper bottling plant in Corisicana, Texas, where he moved with his family.

Naomi and Gail

Harriger was among the attorneys Naomi McGuire and Gail Etheredge worked for in the late 1950s. Etheredge worked directly with Harriger, who was the managing partner.

“Mr. Harriger was the kind who explained everything. He told you why you were doing something,” Etheredge said.

“They taught us as we went along so that we knew what we were doing,” McGuire added.

By the time McGuire arrived in 1958 and Etheredge in 1959 the firm had moved to the Central American Life building, close to their previous offices at the Lubbock National Bank Building. Nelson, McCleskey & Harriger began their lease on the second floor.

They remember Nelson’s booming voice.

“He didn’t mind hollering. I just shook in my boots,” Etheredge said.

But they learned his bark was worse than his bite and continued their careers.

Still, they were careful when it came to Nelson. They were ready to take dictation in shorthand because he didn’t like using recording machines. They screened his calls when he was busy.

Unless, of course, it was someone like Lyndon Johnson, who became vice president in 1961 after winning the presidential election with John F. Kennedy. Johnson became president of the United States after Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and served until 1969.

McGuire remembered taking Johnson’s calls while he was a U.S. senator from Texas. Johnson was Nelson’s good friend, she said.

“Lyndon would call and I would answer the phone. And he would say, ‘Let me speak to Hobert.’ And I might say, well, he’s on another line right now. May I have him call you right back? Then he would say, ‘Go in there and tell Hobert, Lyndon’s on the line,’” she said.

McGuire and Etheredge said they filled all the administrative roles at the law firm — secretary, receptionist, bookkeeper and anything else needing to be done.

“It was a great place to work,” Etheredge said. “I don’t regret any of it. I thoroughly enjoyed it. They earned the respect of their clients and the community. They were top-notch attorneys and gentlemen.”

McGuire agreed. “It was a great place to work, just like Gail said. I never wished I had done something else. They were good people. They were outstanding at work, in the community and with their families.”

Both women graduated from Texas Tech with degrees in business administration.

Careers for women were limited in the late 1950s.

“There were not that many things you could do. You could be a secretary. I didn’t want to be a nurse. I didn’t want to be a teacher. So I chose to be a secretary,” McGuire said.

A placement officer at Tech sent her to interview with the firm and she started work in August, 1958. She would leave to start her family in 1960 and return again in 1968 when her children were a little older.

Etheredge interned as a business machines teacher at a local high school, but didn’t pursue teaching because openings were in smaller towns outside Lubbock. She worked for another law firm briefly. She started with Nelson, McCleskey and Harriger in February, 1959 and stayed until she married in 1964, moving with her husband to Fort Worth. She returned to the firm when they came back to Lubbock a few years later. At an open house, George McCleskey offered her position back and allowed her to work school hours so she could take care of her children.

They both had proved their worth to the firm even in their early years.

Nelson approached both, offering to let them study under a lawyer at the firm, take the bar exam and the firm would pay any expenses. That was one route to become a lawyer in the 1950s.

Both declined, although McGuire would later become a paralegal.

“We both had young children,” Etheredge said.

“We just weren’t sure we wanted that,” McGuire added. “There were not that many women lawyers back then.”

They both remembered the early days of wearing their Sunday best to work — suits, stockings and high heels — and typing perfectly on onionskin paper with carbon copies.

“It was a different atmosphere then. They were very prim and proper. We were not allowed to wear pants. We didn’t have a coffee room. They didn’t socialize with us,” Etheredge said.

McGuire remembers her bosses sending one secretary home who came to work in sandals without stockings.

But as the years progressed, the atmosphere relaxed with each attorney who joined the firm. Eventually they would play bridge at lunch with some of the lawyers who also brought their lunch to work. The earned a coffee room and Christmas parties for the entire staff.

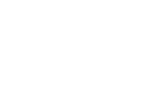

They walked a block along a brick alley to the lunchroom at Hemphill-Wells, a downtown department store.

Ironically, before she married, then-Melissa Harriger was one of the models during a 1970s graduation fashion show at Hemphill-Wells.

At Hemphill-Wells lunchroom, they would have shared space with Lubbock’s “movers and shakers,” who dominated Lubbock’s political life from the 1930s to the 1960s, according to Carlson’s book. The group of downtown power brokers determined who would be the mayor and who would serve on the City Council. They met at a corner table in Hemphill-Wells and included Spencer Wells, the owner of the store, Roy Furr of Furr’s Inc., lawyers, bankers, editors and others, according to Carlson.

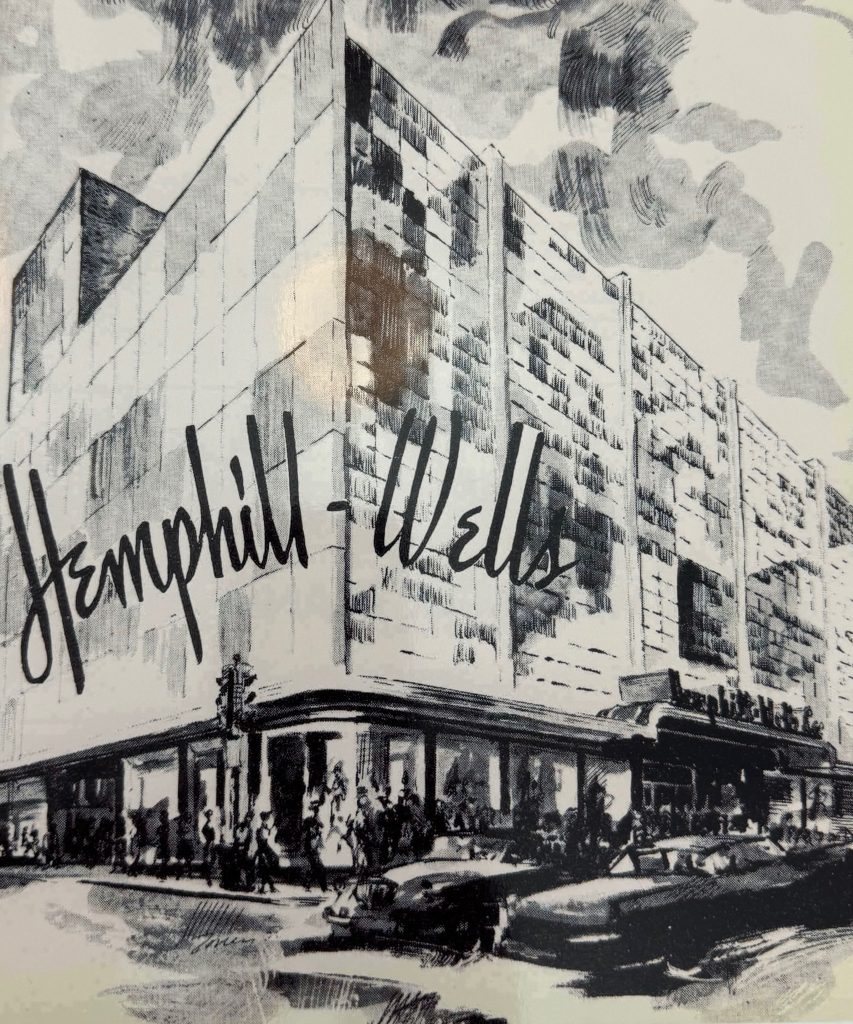

McGuire remembers going to the Hi-D-Ho drive-in, a popular teen hangout, when she was younger and that Buddy Holly played with the band at some of the fraternity parties she attended while at Tech.

“I didn’t think much of it because he wasn’t that famous. You know, he was just one of the band.”

Buddy Holly

The decade saw the meteoric rise – and tragic death – of Lubbock’s Buddy Holly.

Holly and Bob Montgomery, “Buddy and Bob” opened for Elvis Presley who played in 1955 and 1956 at Lubbock’s Fair Park Coliseum.

Holly went on to form the Crickets with Joe Mauldin, Jerry Allison and Niki Sullivan. They released the worldwide hit “That’ll Be the Day,” backed with “I’m Looking for Someone to Love” on May 27, 1957, according to the Texas State Historical Association.

The hits kept coming.

Holly became a solo act but the rock ‘n’ roll pioneer’s life was cut short at age 22 when he died in a plane crash February 3, 1959, in Mason City, Iowa, with Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper – becoming “The Day the Music Died.”

Over the decades, Holly’s influence grew:

- He popularized the Fender Stratocaster guitar, which became a staple for rock bands.

- The Crickets format of singer, guitars, bass and drums became the standard for bands.

- Their music heavily influenced bands such as a Beatles.

His legacy is enshrined in the Buddy Holly Museum in downtown Lubbock and his name adorns Lubbock’s stunning Buddy Holly Hall of Performing Arts & Sciences, which opened in 2021.

Also in the ’50s

- The Korean War, 1950-1953.

- Discovery of the double-helix of DNA.

- The first organ transplant.

- Polio vaccine.

- Two terms of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a WWII war hero.

- Queen Elizabeth II.

- Brown v. Board of Education, 1954, the Supreme Court’s opinion ending racial segregation in public schools.

- McDonalds

- Disneyland

- The transistor radio

- Peanuts comic strip by Charles Schultz

- The first modern credit card, Diners Club

- Velcro