Welcome to the second in a series … this one about the firm’s history in the 1930s. Click here for the first part.

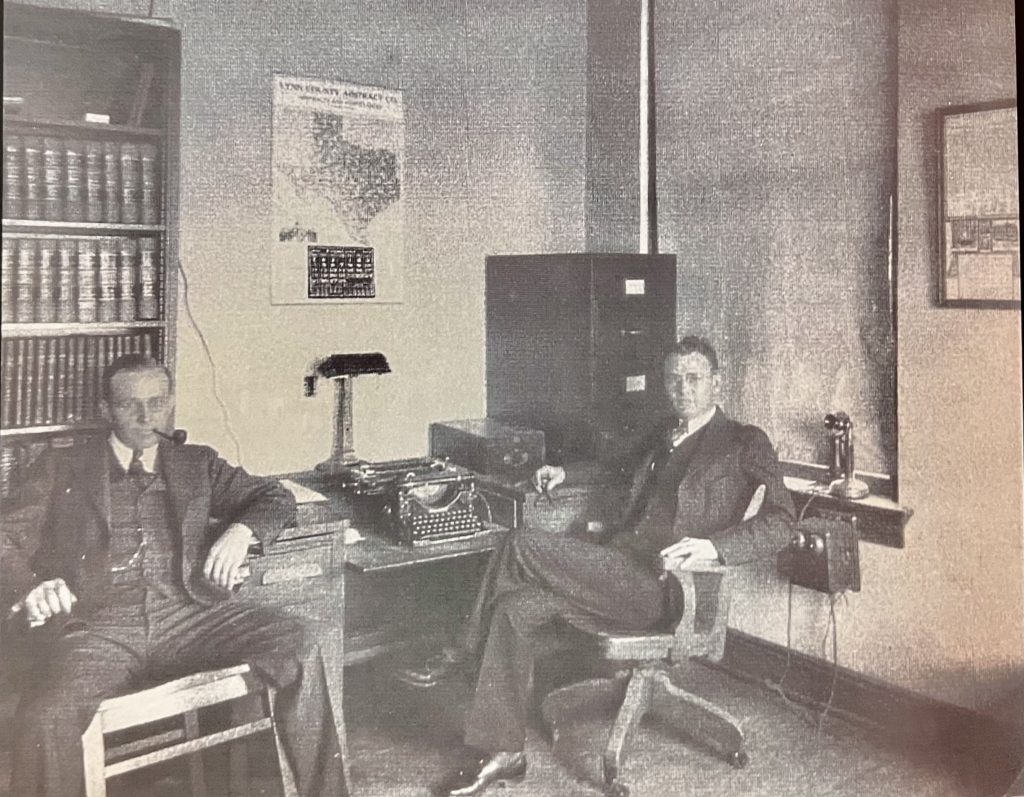

In the photo above, one of the earliest offices of what became the McCleskey Law Firm was in the building to the left of the J.C. Penney Building in downtown Lubbock. This photo is years later.

The 1930s were a bleak decade defined by the Great Depression and exacerbated by the crippling Dust Bowl scattering many West Texans across the country looking for work to support their families.

The 1930s were a bleak decade defined by the Great Depression and exacerbated by the crippling Dust Bowl scattering many West Texans across the country looking for work to support their families.

But Hobert Nelson – now partnering with Truett Smith – kept his fledgling Tahoka law firm afloat.

The firm of Nelson and Smith would decades later become the McCleskey Law Firm.

“The practice of law continually goes on — people are born, people die, probates are filed, lawsuits are filed — even in the midst of what is probably the greatest challenge we’ve had to face,” said Bill Lane, McCleskey attorney.

It also helped financially that Nelson also served as Tahoka City Attorney after opening his practice in 1928. He was elected to two terms as Lynn County Attorney beginning in 1929, before his election as District Attorney in the 106th District comprised of Garza, Lynn, Dawson, Terry, Gaines and Yoakum counties.

Dust Bowl, corruption add to terrible times

The West Texas agricultural economy cushioned some of the immediate blows of the Black Tuesday stock market crash in 1929, but the Dust Bowl’s fierce winds eroded the very foundation of that economy.

Crops failed; people went hungry.

If they required an attorney, some paid with what they had — chickens, vegetables, a mortgage on the farm animals that worked the land, transactions depicted in the iconic 1962 movie, “To Kill A Mockingbird.”

“The effects of the Depression together with the Dust Bowl hit West Texas as the perfect storm,” Lane said.

In Lane’s family’s history, his wife’s grandfather traveled all the way to Washington state to pick apples. Along the way he saw a man sitting on the side of the road with a sign saying: “Please do not pick me up. I voted for Herbert Hoover,” president when the Depression began. One of Lane’s grandfathers followed the harvest to Nebraska with his combine. The other grandfather rode the rails, picking up any odd jobs and sending money back to his family.

“Everyone was in complete survival mode,” he said.

Political corruption in Austin the first half of the decade, especially during the administration of Gov. Miriam “Ma” Ferguson, devastated the legitimate ranks of the Texas Rangers. Notorious criminals like Machine Gun Kelly, Pretty Boy Floyd and Bonnie & Clyde felt safe hiding out in Texas, according to The Texas State Historical Association and Bullock Museum. Convicted West Texas criminals often got pardons. Ferguson issued as many as 100 pardons a month. Critics accused her of accepting bribes for the pardons.

Those pardons could have had a chilling effect on Hobert in his role as a district attorney prosecuting criminal cases during some of Ferguson’s time as governor.

Hobert gets political

In 1935, state Senator Arthur P. Duggan died and Hobert won a special election Sept. 28 that year to replace Duggan.

A year earlier, he was active in helping George Mahon win the newly created 19th U.S. Congressional District, formed after the 1930 Census to serve growing West Texas. The 19th had more than a quarter-million people and about 24,000 square miles.

Mahon, from Colorado City, ran against Judge Clark Mullican, a decorated World War I veteran now living in Lubbock.

Mullican received the second most votes in the first election round of a half-dozen candidates. While he still carried Lubbock in the runoff with Mahon, Mullican lost with 19,000 to Mahon’s 35,000 votes.

Mahon represented the district for 44 years, one of the longest congressional tenures in American history.

Although Mullican had strong Lubbock support, Charles Guy, editor of the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, said Hobert worked with Mahon to undermine Mullican’s hold in the city.

“Young George (he was then 34 years old) couldn’t run an anti-Lubbock campaign himself. That would have been political suicide and would have alienated all the Lubbock vote,” Guy wrote in his editorial column, “The Plainsman,” in 1971.

Guy called Hobert, “a good tough guy” and said he started an extremely well-organized whispering campaign to “keep the Big Town from grabbing everything.”

Hobert and Mahon’s friendship went back at least as far as University of Texas, according to Hobert’s son Bert Nelson.

They both served as district attorneys in nearby districts. And Mahon’s wife, Helen Stevenson, had taught in Tahoka, where Hobert and wife Aileen lived.

The couples remained friends throughout the years, according to a Nelson family memoir.

Bert Nelson tells the story that Mahon asked Hobert if he wanted to run for Congress before Mahon went forward with his plans. Bert said Hobert told Mahon, “I wouldn’t take it if you gave it to me, but I will support you.” He was interested in a state-level office. That story is not mentioned in Mahon’s biography, Janet Neugebauer’s “Witness to History.”

While serving as state Senator, issues Nelson supported included:

- Public education.

- Pensions for seniors.

- Legislation, ultimately unsuccessful, to have a one-house, or unicameral legislature, such as the one in Nebraska.

- Introduced and passed legislation in 1937 to outlaw parimutuel horse racing.

He served in the Senate until 1941.

During that time, in 1938, he ran unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor against Coke Stevenson, who later became Texas governor.

Hobert, a faithful Baptist deacon and Sunday school teacher for 30 years, was fervently against gambling.

When he ran for lieutenant governor, he promised constituents he would abolish legalized gambling and open saloons.

In the Legislature, when the final vote didn’t look promising to end parimutuel horse racing, he enlisted the support of a family whose father had squandered their finances gambling. Before the vote, he carried the young daughter on his hip into the chamber to put a face to the suffering gambling created.

His bill passed by one vote.

In 1983 before he died, Nelson read a news story that the Texas House had once again defeated parimutuel horse racing. Satisfied, he said to his family, “I told you they would never pass that during my lifetime.”

Other things happened in the 1930s that were not all Depression and Dust Bowl

- High Plains favorites Bob Wills – the King of Western Swing – and His Texas Playboys crooned, “Sitting on Top of the World.”

- Amelia Earhart completed her first non-stop solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean, a first for a woman. She also flew solo across the Pacific but disappeared when she attempted to circumnavigate the globe.

- The first drive-in movie theater opened in New Jersey.

- Cartoon characters Mickey and Minnie Mouse, Donald Duck, Popeye and Betty Boop all make their first appearances.

- R.R. Tolkien’s “The Hobbit” is published.

- $100 in 1930 is worth $1,586 in 2021. A gallon of gas was 10 cents in 1939 and steak cost 20 cents a pound.

New Deal comes to West Texas

By the mid-1930s New Deal programs, implemented after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election in 1932, were beginning to somewhat ease the Depression’s burden. Evidence of Works Progress Administration programs can still be seen in state parks, roads and bridges as well as murals.

- More than 50,000 Texas men gained employment in the Civilian Conservation Corps. They earned $30 a month ($25 was sent back to their families) for two six-month terms of outdoor labor.

- The Rural Electrification Administration brought power to many South Plains farmers and other rural residents in the second half of the 1930s. Lubbock area farmers formed their own local co-op that came to be known as the South Plains Electric Cooperative.

- In Lubbock, Mackenzie Park, a base for a CCC camp, benefited from the program. CCC laborers also worked to reverse the farming practices worsening the Dust Bowl with soil conservation measures.

- The WPA funded a dig at the Lubbock Lake site in 1936 and archaeological discoveries prompted more funding.

Not all the aspects of the New Deal were popular. Repealing prohibition with the 21st Amendment was unsettling to many in West Texas. After the state Legislature ratified the amendment, they left decisions to individual counties about whether to authorize the sale of wine, beer and liquor.

The Nelsons move to Lubbock

During the second half of the 1930s, Hobert moved his law practice to Lubbock. Hobert and Aileen bought a house on 17th Street, a few blocks from Texas Technological College.

Truett Smith stayed in Tahoka. As a judge he presided over one of last capital rape cases in Texas of Bennie Lee McIntyre, then an 18-year-old African American, who confessed to the crime. Although most agreed his legal defense was inadequate, he was electrocuted in Huntsville in 1963. His crime and trial were common in courts across the country and the issues were immortalized in the aforementioned, “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Federal rulings in 1973 eliminated rape as a capital crime, because of trials like McIntyre’s.

The first time Hobert showed up in the Lubbock City Directory is 1937 and he partnered with Clark Mullican – the same Clark Mullican he helped Mahon defeat a few years earlier in the congressional election.

In Neugebauer’s 2017 Mahon biography, she writes the political temperament of the ‘30s was very different than now. Political opponents could become political allies after an election.

After his defeat, Mullican extended congratulations and friendship to Mahon and told the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal “the voice of democracy has spoken and everybody should stand behind him (Mahon) and move on,” Neugebauer wrote.

Hobert and Mullican first opened an office at 909 1/2 Broadway, on the south side of Broadway across from the courthouse. Those buildings have long been torn down and the block is now the site of – ironically – the George H. Mahon Federal Building, built in the early 1970s.

Mullican was born in 1887 in Ellis County to a successful farmer and stockman. He was one of four surviving children in his family. He began military school in 1901, followed by studies at Texas Christian University and the University of Texas. He was admitted to the bar in 1909, practiced law in Dallas and was an assistant district attorney in 1913 and 1914.

World War I began in July 1914. After the United States entered the war in April 1917, Mullican helped organize volunteer guard companies in Dallas and Fort Worth and seven communities south of what is now the Metroplex. They became the Thirty-Sixth Infantry Division.

Mullican accompanied these troops to France in 1918 where they were part of the 144th Infantry regiment.

He fought battles in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which stretched all along the Western Front. The three-stage final offensive was one of the deadliest military campaigns of the U.S. Army. More than 26,000 American lives were lost.

Mullican was promoted to lieutenant colonel for gallantry in action, given command of his unit and soon the entire 144th regiment. The commander of the French armies in the east awarded him the Croix de Guerre. He returned to Texas with his regiment as a colonel, serving until it was demobilized in July 1919, when he moved to Lubbock, where his father and family had moved three years earlier.

He established a law firm with state Senator William Bledsoe, the “father” of Senate Bill 103 creating Texas Tech.

Mullican soon accepted an appointment as judge of the 72nd District until 1927 and then accepted an appointment to the new 99th District. Both districts were administered in the Lubbock County Courthouse.

While a judge, Mullican presided over the trial of two cattle rustlers who murdered field inspectors for the Southwestern Cattle Raisers Association. The men were sitting in the lobby of a hotel in Seminole the day before they were to testify. The two suspected cattle thieves came in and shot them, according to the online Officer Down Memorial Page.

The men were convicted and given long sentences, but both escaped prison. One committed suicide a few years later after killing another man and the other was pardoned by the Texas governor, but it’s not known if it was one of “Ma” Ferguson’s many controversial pardons.

Mullican resigned from the bench in 1936 to return to private practice.

His partnership with Nelson lasted a couple of years.

In the 1939 Lubbock City Directory, Nelson moved two blocks west and across the street to partner with Frank Brown in the Leader Building, 1104 Broadway, next to the JC Penney Building.

Mullican practiced law until 1947 and passed away in 1950.