Welcome to the third in a series … this one about the firm’s history in the 1940s.

Click here for the first part.

Click here for the second part.

In the photo above, George McCleskey in uniform.

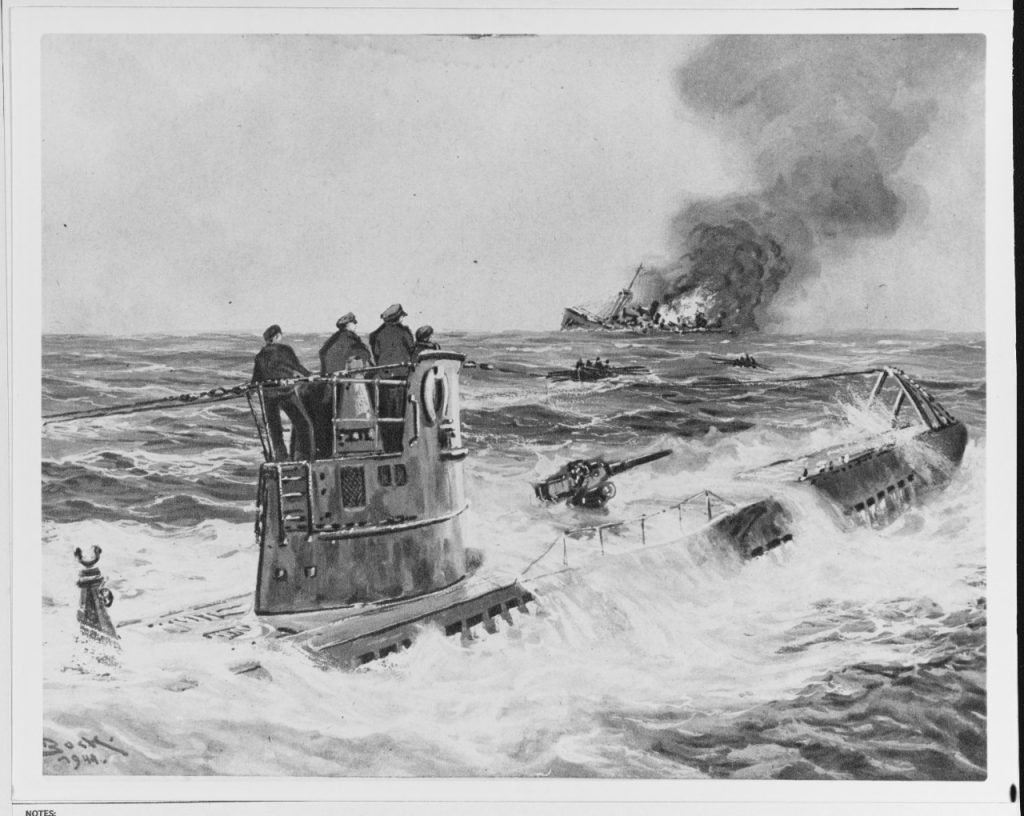

Merchant ships cutting through cold and deep North Atlantic waters during World War II sailed a dangerous route from the United States to the Russian Arctic Circle port of Murmansk.

Gunnery Officer George W. McCleskey was on those missions to deliver weapons and supplies, hoping to keep German U-boat submarines and aircraft from blowing them – and their vital cargo – out of the water.

Gunnery Officer George W. McCleskey was on those missions to deliver weapons and supplies, hoping to keep German U-boat submarines and aircraft from blowing them – and their vital cargo – out of the water.

McCleskey developed a mathematical formula to aim and shoot anti-aircraft guns that impressed his superiors. They brought him back to the safer stateside to teach what he developed.

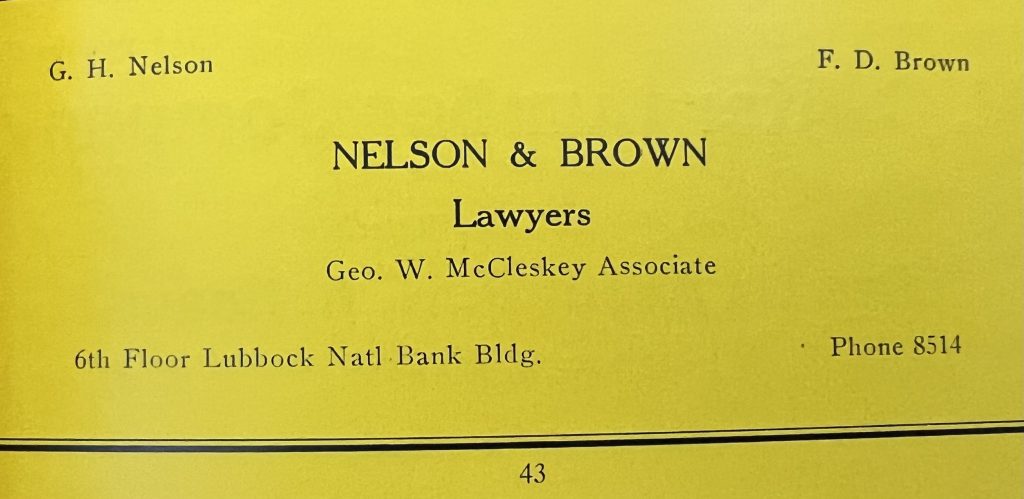

After the war ended, McCleskey returned to Lubbock to practice law with the firm of Nelson and Brown.

Hobert Nelson and Franklin Brown added McCleskey as an associate in 1940. He enlisted in the Navy the following year after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor – like many young men whose patriotism compelled them to stand up against the Axis powers and protect their country.

Nelson and Brown not only kept McCleskey’s job open, but they paid his salary through the war years. In Lubbock’s 1943 and 1944 city directories, McCleskey is listed as an associate with Nelson & Brown.

Their investment may have been the right and patriotic thing to do, but it also paid off – today McCleskey is the law firm’s brand.

Lubbock prepares for war

Even before Pearl Harbor, Lubbock was getting ready for war.

The U.S. Department of War and U.S. Army built Reese Air Force Base, just west of Lubbock in August 1941, during the defense buildup. It was originally known as the Lubbock Army Airfield.

War had been raging in Europe since Sept. 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland.

According to historian Paul H. Carlson in his book, “The Centennial History of Lubbock: Hub City of the Plains,” the city had purchased the land — 1,400 acres — for military use. The military trained pilots to fly advanced twin-engine and other multiple engine airplanes.

British Royal Air Force cadets flew from their training base in Terrell, Texas – east of Dallas – to Lubbock, close to the same distance they’d fly in missions from Cork, Ireland, to London, England.

East of Lubbock, a second training base opened, the South Plains Army Air Field. It became the largest advanced glider pilot training base, where 80 percent of all Allied glider pilots trained. Today, the Silent Wings Museum at Lubbock’s Preston Smith International Airport, honors those glider pilots.

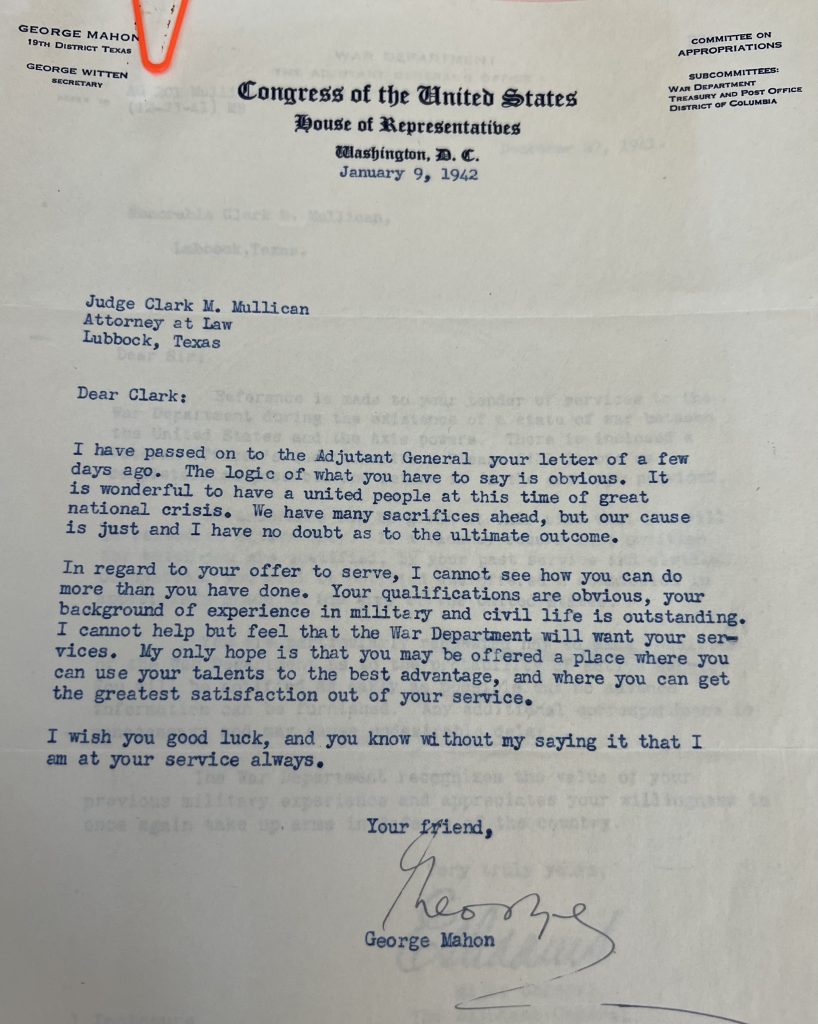

Lubbock’s U.S. Representative George Mahon pushed for the timely acquisition of the air bases, Carlson wrote. He was on the Congressional Appropriations Committee and its subcommittee for War Department appropriations.

After the war, having the military bases helped Lubbock’s post-war economy.

Mahon was a lifelong friend of Hobert Nelson.

McCleskey gets to law school after surviving Depression

McCleskey’s son – George H. McCleskey, born in 1944 – recalled stories his father told him about his early years and the war.

“It’s what I understand from my memory, which is from a long time ago,” he said.

George W. McCleskey was born in 1915 in Rush Springs, Okla., but grew up in Clarendon, Texas, about 60 miles east of Amarillo, where his family moved during the Depression. His father – who also went by George H. McCleskey – was a banker. Three banks he managed went broke. He went personally broke trying to salvage the banks.

McCleskey remembers his grandparents living in an apartment over a drugstore, where his grandmother took in laundry and baked cakes and pies to help support her family.

“He and his brother, David, were pretty small children when they moved to Clarendon. Most of their growing up years they were pretty poor. When my dad went off to college, he worked and sent money home during the Depression for his folks,” said McCleskey, who lives in the Metroplex.

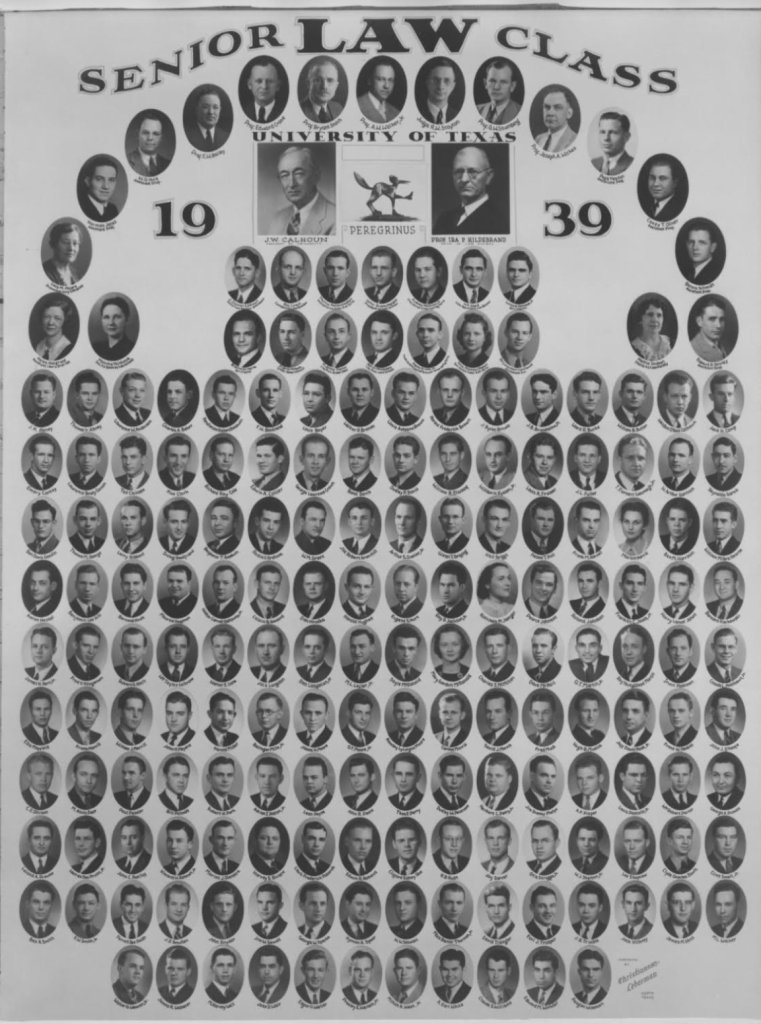

His father graduated from Clarendon High School, then from North Texas State and finally law school in 1939 from the University of Texas.

The senior McCleskey studied with a distinguished group of classmates. One was John Connally, who served as governor of Texas from 1963-1969. On Nov. 22, 1963, Connally was riding in a Dallas motorcade with President John F. Kennedy when shots from a nearby building killed Kennedy and critically wounded Connally.

The senior McCleskey studied with a distinguished group of classmates. One was John Connally, who served as governor of Texas from 1963-1969. On Nov. 22, 1963, Connally was riding in a Dallas motorcade with President John F. Kennedy when shots from a nearby building killed Kennedy and critically wounded Connally.

(Connally later vetoed plans for a medical school at Texas Tech, that finally passed when Tech grad Preston Smith followed Connally as governor.)

Another classmate was Reynaldo Garza, the first Hispanic judge in Texas who also started a law school bearing his name in the Rio Grande Valley.

After he graduated, McCleskey and another attorney established a law practice in Lamesa, about 60 miles south of Lubbock. “They were in a house that had two rooms,” the younger McCleskey recalled. “They practiced law in one room and lived in the back room.”

George W. McCleskey’s path crossed those of Hobert Nelson and Franklin Brown while trying cases. Both attorneys were so impressed they recruited him to their practice in Lubbock.

A year after joining the firm in 1940, he wed Mary Belle Hall.

The McCleskey Brothers go to war

After Pearl Harbor, McCleskey’s brother David enlisted in the Air Force along with his brother joining the Navy.

After brief training in Norfolk, Va., McCleskey took his post as gunnery officer on the merchant supply ships as America joined the ongoing Battle of the Atlantic, one of the war’s longest battles from 1939 to 1945. German U-Boats came close to the Eastern Seaboard.

Even though the Allies prevailed, they lost 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships in the Atlantic, while Germans lost 783 U-boats and 47 surface ships, according to Naval History and Heritage Command.

McCleskey told his son the greatest danger on those voyages to Russia was the Germans could tell the ships were loaded because they sat low in the water.

The civilian captain of the merchant ship was in charge unless it was attacked. Then the chief gunnery officer — McCleskey’s job — took command.

The younger McCleskey said his father told him he came up with his formula to improve anti-aircraft performance because “You get pretty smart when you’re in the North Atlantic and you are worried about seven or eight enemy aircraft.”

McCleskey was promoted to lieutenant commander and ended his war career at the Pentagon.

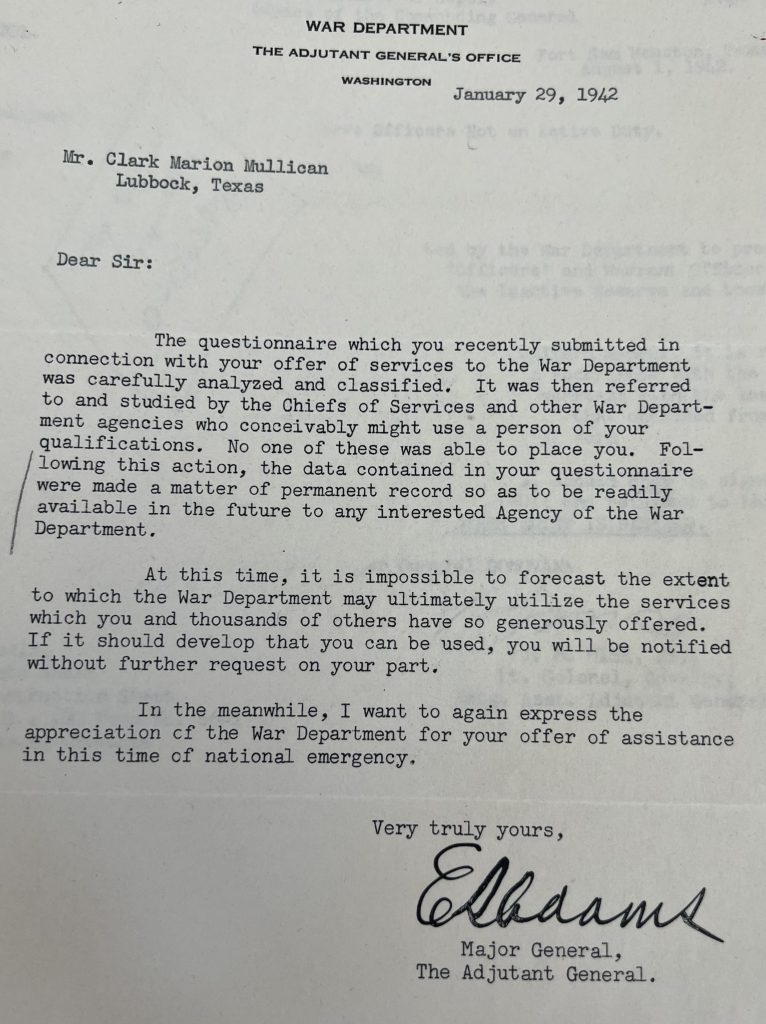

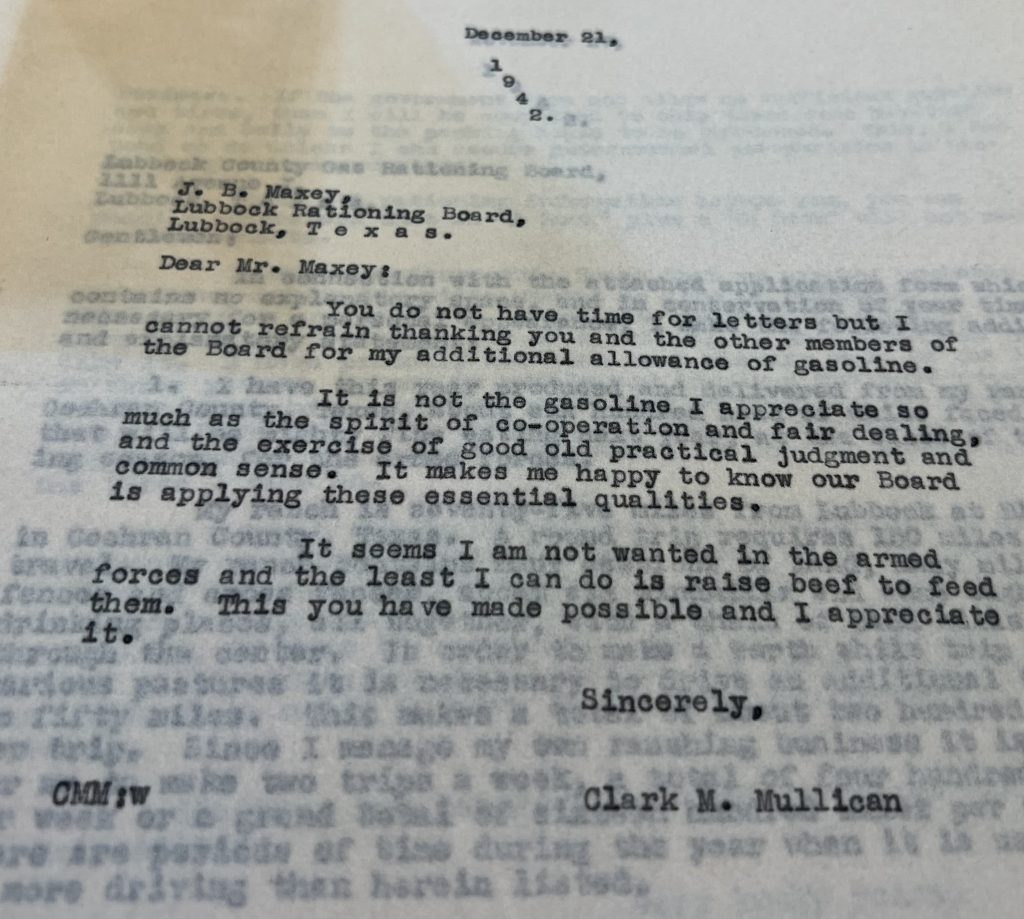

Clark Mullican, who practiced with Nelson for a short time the previous decade and served in WWI, tried to get back into active service during WWII. He was in his 50s and more than a decade older than Nelson. He even wrote Mahon for help, but finally gave up.

Lubbock struggles through war, then thrives

Just as McCleskey’s star was rising in the 1940s, Lubbock was also rising — becoming a larger urban area.

The population of the city increased 125 percent during the decade from 1940, 31,853 to 71,747 in the 1950 census.

Life on the South Plains and in Lubbock, like the rest of the world, was challenging during the war.

People who were used to doing without during the Great Depression also suffered the deadly losses war brings.

According to Chuck Lanehart, a lawyer and historian, writing for the Caprock Chronicles in the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: “Among 22,000 Texas servicemen killed or missing from 1942-45, about 800 were South Plains residents.”

People in Lubbock supported their troops and got behind the war effort at home. New cars, houses and appliances weren’t

available because those resources were allocated to winning the war.

Meat, sugar, coffee, nylons, shoes, rubber and auto parts were rationed and gasoline was only available in limited quantities on certain days, Lanehart wrote.

Mullican made requests for enough gasoline for his Chevrolet pickup truck to get to his farming and cattle business in Cochran County.

Like many others in Lubbock, Hobart Nelson and his wife, Aileen, planted their annual garden, likely calling it a Victory Garden and canned their abundant vegetables and fruit.

South Plains agriculture and oil production flourished.

Cotton farmers almost tripled their earnings on their crop, from $997 in 1939 to $2,894 in 1945, Lanehart wrote.

Harvard-educated historian and writer Doris Kearns Goodwin, reflected on this boon in one of her many essays. “America’s response to World War II was the most extraordinary mobilization of an idle economy in the history of the world. During the war 17 million new civilian jobs were created, industrial productivity increased by 96 percent, and corporate profits after taxes doubled.”

The innovations and inventions of the war came home afterward. Jeeps, microwave ovens, color televisions, early computers and aerosol spray cans became available to consumers.

During the war years and after people in Lubbock listened to news and music on KYFO — maybe hearing news of the war from broadcaster Edward R. Murrow.

Songs from the 1940s included hits like “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” by the Andrews Sisters, “Chattanooga Choo-Choo,” by Glenn Miller Orchestra and “Don’t Fence Me In,” by Gene Autry.

At Lubbock’s Hutchinson Junior High School, a young Buddy Holly (born in 1936), made friends and schoolyard music with Bob Montgomery in the group Buddy and Bob. They played gigs around town and eventually got a weekly show on KDAV radio.

Holly’s brothers, Larry and Travis, were serving in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific. Larry brought a guitar home and would teach his little brother to play. Buddy’s influence in rock ‘n’ roll lived on long after he tragically died in a 1959 plane crash.

Another soon-to-be-famous Lubbock musician, Mac Davis, was born Jan. 21, 1942.

When victory was declared in Europe, May 5, 1945, Lanehart wrote Lubbock went to church to pray — more than 2,000 people attended churches that day. “Residents realized V-E Day was but a partial victory and seemingly held their breath for the final victory.”

The citizens and surrounding troops got their chance to dance in the streets three months later when victory over Japan was declared, August 14.

The newspaper described the celebration of people rejoicing, cars honking and church bells ringing as “hog wild, pig crazy.”

Not everyone came home from the war.

David McCleskey was killed in Europe.

George W. told his son that when the war was over, he, like many other sailors, planned to walk west with an anchor until people didn’t know what an anchor was.

“But, of course, that wasn’t a true story because he came back to Lubbock,” McCleskey said. “He could have been an engineer. He was pretty bright in those areas.”

Now it’s Nelson, Brown & McCleskey

McCleskey came home to his family and his law practice. In the 1945 City Directory, the firm was now called Nelson, Brown & McCleskey.

He was a:

- Talented lawyer and litigator, who earned his ranking in the firm through the cases he won.

- Faithful Baptist and shared his beliefs with anyone who was interested. “My dad was a very, very devout Christian and he practiced what he preached,” said the younger McCleskey. At some point in his career, the older McCleskey considered going part time with his law practice to do more lay preaching.

- Teetotaler who never drank alcohol. He insisted his soft drinks were served in their bottles, so no one would think he was having a mixed drink.

- Hard worker, who most every evening brought home a briefcase full of work.

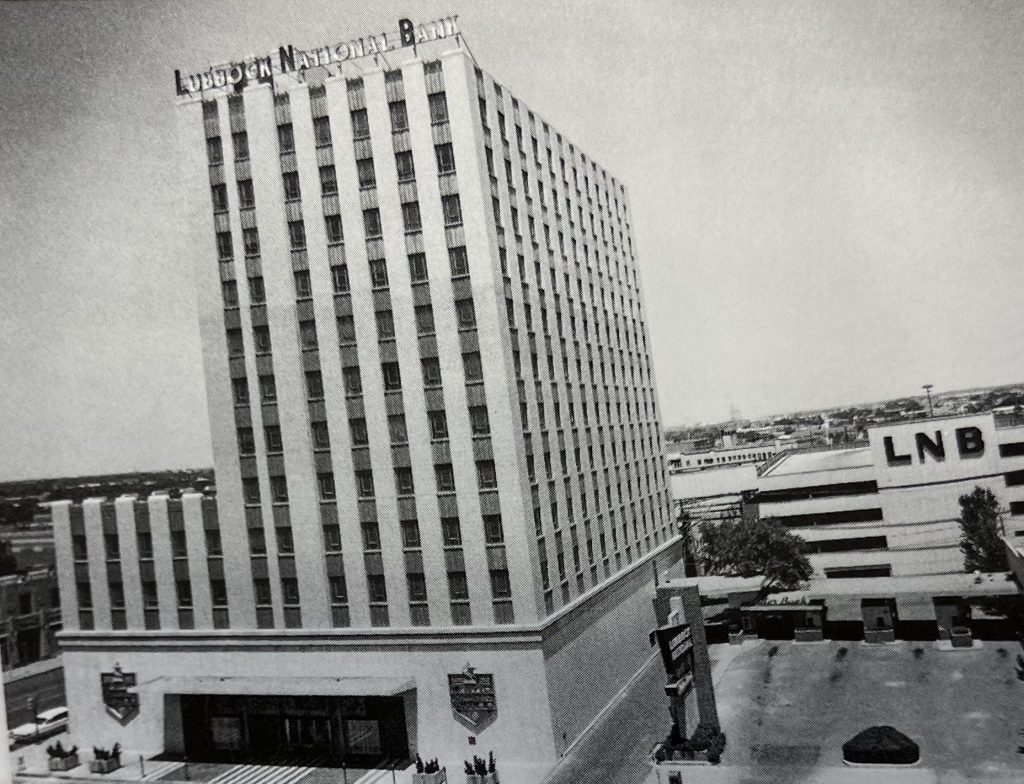

The younger McCleskey remembers visiting his father when the law firm’s offices were in the old Lubbock National Bank building.

He didn’t particularly enjoy visiting because the dentist he had to see for problems with his baby teeth was in the same building.

He remembered watching parades from his dad’s office after the firm moved to the old Citizen’s Bank building.

Although his dad didn’t discuss much about his work, the younger McCleskey understood his dad and his law partners had very different personalities, especially after he joined the firm in 1976.

“I heard stories, each of those guys had extremely strong personalities.”

The older McCleskey was confident, self-assured and a perfectionist.

Hobert Nelson was an old-style trial lawyer — blustery and aggressive.

For example, if you irritated Hobert, he would tell you about it, while McCleskey would get quiet.

Frank Brown was a scholar. “He was not a courtroom guy, but my dad always said if you had any issue at all you asked Frank Brown and he would not only tell you all the cases involved, but he could also tell you the citations.”

By 1946, Brown left and the firm was Nelson, McCleskey & Howard. But a year later, it was Nelson & McCleskey.

Nelson and McCleskey practiced together long after the 1940s, but they had their moments.

“There was never any issue about whether they would remain partners or not, (but) they would sometimes go weeks without speaking to each other if they got crossways on an issue,” the younger McCleskey said.

Along with his devotion to the Baptist church and Christianity, McCleskey belonged to numerous civic groups, including the Kiwanis and the Chamber of Commerce. He was an avid trout angler, fishing streams in his waders in northern New Mexico and southern Colorado.

“He liked to fish standing on the ground, not on a boat,” the younger McCleskey remembered. His father had spent enough time on ships in the dangerous North Atlantic.

“He loved to fly fish. He taught other people how to fly fish.”